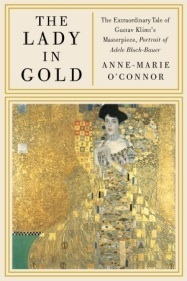

The past three borrowed books that I have digested reveal themselves to be as much about world history as the history of art. The Lady in Gold: The Extraordinary Tale of Gustav Klimt's Masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer by Anne-Marie O'Connor; Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X by Deborah Davis; and Stealing the Mystic Lamb: The True Story of the World's Most Coveted Masterpiece by Noah Charney. The common thread in all of these tomes is actually not the fate of the art nor the artists, but the unspeakable fate that befell Hitler's human victims. As enlightening as these books are, I cannot recommend them for a light summer read.

So what draws me to such books? Iconic images that continue to impact our world, famous artists who are household names, and a desire to better understand how art and its time interact.

Case in point: Klimt's "The Kiss" is repeated, reinvented, and reissued in every imaginable form, from coffee table book to coffee mug to museum print. It is now one of those ubiquitous images that we all know but no longer see. How can we bring fresh eyes to "The Kiss," the "Mona Lisa," "Vitruvian Man," or any masterpiece turned advertising staple?

Yet the artist is able to bring a fresh eye in creating his original. For example, the introduction of gold leaf and a personal iconography into Klimt's work is purportedly influenced by his visit to San Vitale Basilica - where he beheld Byzantine gold mosaic tile shimmering around the visage of Empress Theodora. But it was the prestige of being painted by one of Austria's premier artists that drew the sitter for "Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer" and Klimt together, at a time when portraiture took years - three, in fact. When the commission was complete, its 1908 unveiling was not only to Adele and her husband, but to Austrian society as well.

A similar scenario unfolded 24 years earlier for John Singer Sargent at the 1884 Paris Salon with the unveiling of his portrait of Virginie Gautreau. Neither portrait now shocks our modern sensibilities, but in the context of their day, they pushed the edge of their era's "envelope." Adele's body melds into an abstraction of form and symbols while seductive eyes gaze unabashedly at the viewer; Virginie's highly-coutured and contoured body flaunts a fallen shoulder strap. Both portrayals are sensational in every sense of the word. Today, we barely react to the shock value of oversized nudity in the up-close-and-too-personal style of popular artists such as Jenny Saville.

Speaking of nudity, it is Jan (and Hubert) Van Eyk's Adam and Eve who upstage much of the work on the 12-paneled Ghent altarpiece (completed in 1430-1432 for the now St. Balvo Cathedral). The degree of realism in these nearly life-size figures caused a stir for centuries, eventually resulting in reproductions to replace the two offending panels. Adam and Eve are clothed in animal skin; sanitized for the changing times.

Personally, I am disappointed that the story of the actual painting of the altarpiece, and of the two portraits, encompasses only the first few chapters of each book. The authors then quickly move onto lengthy discussions of heirs, provenance, and religious, military, and political history. Could the Ghent altarpiece speak, oh, the tales it would tell about the attempts on its life and the desires of its many masters for domination, including imprisonment in a salt mine by Hitler's henchmen. Hitler coveted art - his rejection and frustration as a young artist perhaps a motivation - to a degree that endangered the very things he sought to secure. Among these is Klimt's portrait of Adele. Through heroic efforts, all three artworks survive to confound and entice us; to only partially answer our queries.

After willing myself through the chapters on the human atrocities that occur alongside the travails and travels of the paintings, I find that I care less and less about these "masterpieces." O'Connor's closing chapter speaks eloquently to my own thoughts. "What is the value of a painting that has come to evoke the theft of six million lives?" How many artists never had the good fortune to create their masterpiece? Heavy reading, not recommended for the beach.

So what draws me to such books? Iconic images that continue to impact our world, famous artists who are household names, and a desire to better understand how art and its time interact.

Case in point: Klimt's "The Kiss" is repeated, reinvented, and reissued in every imaginable form, from coffee table book to coffee mug to museum print. It is now one of those ubiquitous images that we all know but no longer see. How can we bring fresh eyes to "The Kiss," the "Mona Lisa," "Vitruvian Man," or any masterpiece turned advertising staple?

Yet the artist is able to bring a fresh eye in creating his original. For example, the introduction of gold leaf and a personal iconography into Klimt's work is purportedly influenced by his visit to San Vitale Basilica - where he beheld Byzantine gold mosaic tile shimmering around the visage of Empress Theodora. But it was the prestige of being painted by one of Austria's premier artists that drew the sitter for "Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer" and Klimt together, at a time when portraiture took years - three, in fact. When the commission was complete, its 1908 unveiling was not only to Adele and her husband, but to Austrian society as well.

A similar scenario unfolded 24 years earlier for John Singer Sargent at the 1884 Paris Salon with the unveiling of his portrait of Virginie Gautreau. Neither portrait now shocks our modern sensibilities, but in the context of their day, they pushed the edge of their era's "envelope." Adele's body melds into an abstraction of form and symbols while seductive eyes gaze unabashedly at the viewer; Virginie's highly-coutured and contoured body flaunts a fallen shoulder strap. Both portrayals are sensational in every sense of the word. Today, we barely react to the shock value of oversized nudity in the up-close-and-too-personal style of popular artists such as Jenny Saville.

Speaking of nudity, it is Jan (and Hubert) Van Eyk's Adam and Eve who upstage much of the work on the 12-paneled Ghent altarpiece (completed in 1430-1432 for the now St. Balvo Cathedral). The degree of realism in these nearly life-size figures caused a stir for centuries, eventually resulting in reproductions to replace the two offending panels. Adam and Eve are clothed in animal skin; sanitized for the changing times.

Personally, I am disappointed that the story of the actual painting of the altarpiece, and of the two portraits, encompasses only the first few chapters of each book. The authors then quickly move onto lengthy discussions of heirs, provenance, and religious, military, and political history. Could the Ghent altarpiece speak, oh, the tales it would tell about the attempts on its life and the desires of its many masters for domination, including imprisonment in a salt mine by Hitler's henchmen. Hitler coveted art - his rejection and frustration as a young artist perhaps a motivation - to a degree that endangered the very things he sought to secure. Among these is Klimt's portrait of Adele. Through heroic efforts, all three artworks survive to confound and entice us; to only partially answer our queries.

After willing myself through the chapters on the human atrocities that occur alongside the travails and travels of the paintings, I find that I care less and less about these "masterpieces." O'Connor's closing chapter speaks eloquently to my own thoughts. "What is the value of a painting that has come to evoke the theft of six million lives?" How many artists never had the good fortune to create their masterpiece? Heavy reading, not recommended for the beach.